#41 John Law and the Mississippi bubble

Brief notes on economic and financial history: Episode II

Today we look at one of the early monetary experiments in the history. We travel to the France of the XVIII century and trace the source of the Mississippi bubble and its subsequent collapse. We look at John Law’s ambitious monetary experiment and, in particular, his policy of expanding France’s money supply and cutting interest rates. Law conducted one the world’s first experiment with easy money. His story of boom and bust is a cautionary tale for our times.

“Tis not altogether improbable, that when the nation become heartily sick of their debts, and are cruelly oppressed by them, some daring projector may arise with visionary schemes for their discharge. And as public credit will begin, by that time, to be a little frail, the least touch will destroy it, as happened in France; and in this manner it will die of the doctor”

David Hume. Of Public Credit, 1752

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

John Law was a Scottish economist who played a significant role in the financial affairs of France during the early 18th century and is considered a pioneer of monetarist economics, foreshadowing some of the ideas of Milton Friedman. His monetary policies formed the foundation of modern central banking. However, Law's "System", as he referred to it, ultimately proved to be a failure with the eruption of the Mississippi Bubble, leading to the discredit of both his project and monetary ideas.

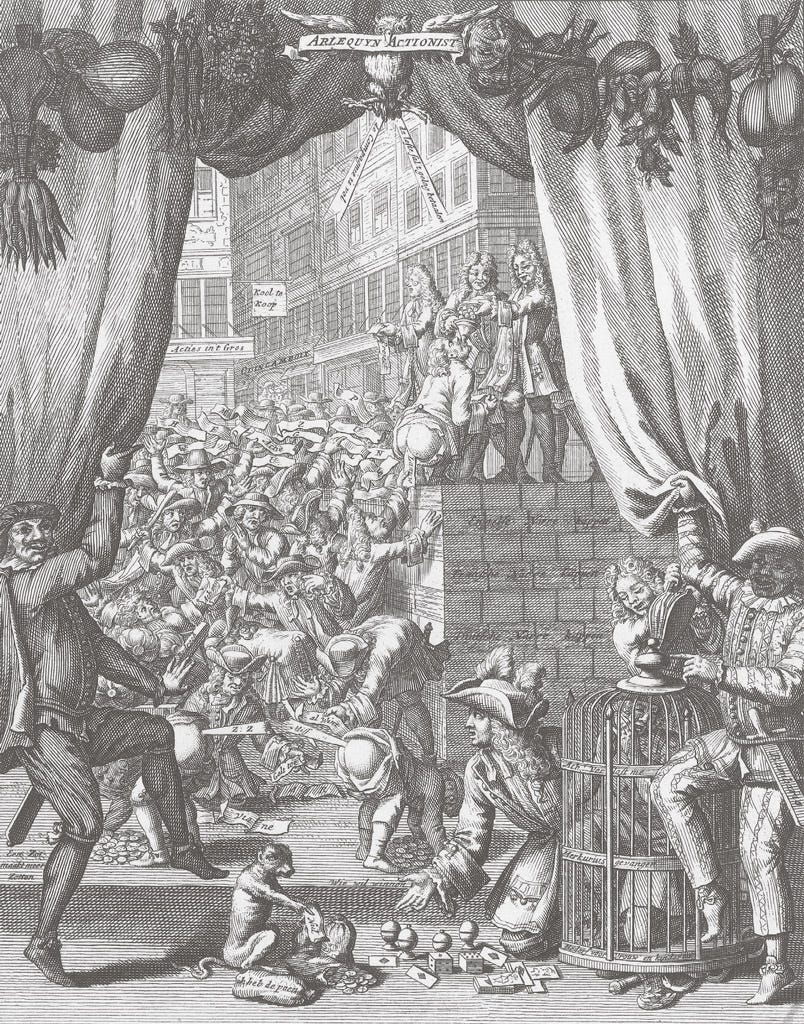

While the bubble is often attributed to the madness of crowds and the frenzied speculation on the Parisian open-air stock market that took place in the rue Quincampoix, this outbreak of speculative fever wasn’t a random event.

The same old same old

Law believed that “Money is not the Value for which Goods are exchanged, but the Value by which they are exchanged.” Essentially, he believed that because money lacks inherent value, it does not have to be backed by gold or other valuable materials.

Throughout his writings, Law emphasized that trade relies on the circulation of credit and that a lack of money can hinder the availability of credit. He proposed the creation of a bank that would issue paper money backed by land, rather than gold or silver, as a means of achieving prosperity. This idea of separating money from precious metals opened the possibility for a controlled currency.

Law tried multiple times to get governments to adopt his land bank scheme, but was consistently rejected by the English, Scots, Duke of Savoy, and Louis XIV of France. However, Law's luck finally changed when Louis XIV died and the Regent of France, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, took power. The Regent was more open to new ideas and was facing a dire financial situation due to the previous king's wars. France's debts were equivalent to its annual output and tax revenues couldn't cover interest payments, leading to discounted debt prices. Sounds familiar?

Taking advantage of the opportunity, Law suggested that France had two major issues: excessive debt and high interest payments on that debt. To address these problems, he proposed the creation of a national bank.

“The bank is not the only nor the biggest of my ideas – I will produce a work which will surprise Europe by the changes that it will generate in France’s favour, changes which will … establish order in its financial situation, to restore, provide for, and increase agriculture, manufactures, and trade, to increase the size of the population and the general revenue of the kingdom, to repay the useless and onerous ‘charges’, to increase the King’s revenues while caring for the people, and to reduce the state’s indebtedness without hurting its creditors.”

An abundance of money which would lower the interest rate to 2% would, in reducing the financing costs of the debts and public offices, etc., relieve the King. It would lighten the burden of the indebted noble landowners. This latter group would be enriched because agricultural goods would be sold at higher prices. It would enrich traders who would then be able to borrow at a lower interest rate and give employment to the people.”

In plain English, Law was proposing that a central bank could stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates through the printing of more money. This would provide relief for heavily indebted borrowers, generate employment, and boost economic activity. Additionally, the expense of paying off government debt would decrease and deflation would cease. What a visionary! The same response as our central bankers in 2008.

In May 1716, the Regent's Council approved the establishment of a private bank called the General Bank. The Regent himself became a major shareholder and issued a decree making the bank's notes acceptable for paying taxes.

The Mississippi Company

But a private bank was not enough to implement all his ideas. One year later, he took over the Mississippi Company, which held monopoly trading rights and land claims to French Louisiana, with France's other trading monopolies, the tobacco monopoly, and the contract to farm royal taxes and the mint. He also arranged for the Mississippi Company to take over France's national debt in exchange for annual payments. In a few years, Law had created a powerful financial entity known as the System, comprising commercial, debt management, and banking operations.

Initially, shares in the Mississippi Company were offered to the public at 500 livres, with investors able to pay for three-quarters of their subscription with depreciated government debt. The General Bank, which Law had previously established, was nationalized and renamed the Royal Bank in December 1718. This bank, unlike the General Bank, issued its notes in the unit of account, the livre tournois, rather than gold, allowing an unlimited amount of money to be printed.

Initially, the stock value remained stable, but after Law increased the money supply, the value of Mississippi shares shot up, reaching almost 10,000 livres. This sparked a frenzy of speculation in France and Europe, with chaotic scenes in the Parisian open-air stock market, the rue Quincampoix, recorded in some contemporary memoirs.

“There were crowds all day long … such wild excitement was never known before … Day by day, Law’s bank and his joint stock company gained in favour. People trusted both completely, rushing to turn their estates and houses into paper, with the result that everything but paper cost more … Everyone’s head was turned.”

In a world turned upside down, even servants were speculating in the rue Quincampoix on their own account, rather than executing their masters' trades. In late 1719, an edict was even issued prohibiting liveried servants from wearing luxurious clothing such as velvet sleeves, silk shirts, large silver buttons, and golden cloth. It was a wild and crazy time, indeed.

The bubble

Law was a master of financial manipulation, a skill more or less equivalent to being a modern-day stock-jobber. He boosted demand for Mississippi Company shares by requiring applicants for new issues to already own shares from earlier subscriptions. As each new subscription was issued at a higher price than the previous one, it was best to get in early. The shares were issued on a partly paid basis, with only a small down payment required, so speculators' profits were highly leveraged to movements in the share price.

But the main reason for the bubble was the Royal Bank's money printing. Over the course of 1719, the amount of paper money in circulation increased by around a billion livres. The bank even had to employ eight printers to produce the high-denomination notes. The printing was so intense that the cashier's handwritten signature had to be replaced with a printed impression. The demand for both shares and banknotes was so high that the manufacturers couldn't even keep up with the demand for paper!

By May 1720, the total amount of banknotes in circulation had reached 2 billion, a fifty-fold increase from the issuance of the General Bank and roughly double the quantity of gold and silver coins in circulation.

In his earlier writings, Law had argued that East India Company shares were similar to money because they could be used to settle debts. Under his system, both bank money and Mississippi stock became interchangeable. The Royal Bank provided loans to speculators with Mississippi stock as collateral at a 2% interest rate. The Mississippi Company also purchased large amounts of its own stock using loans from the Royal Bank. In an effort to boost the share price, the company offered to buy back shares at a 10% premium in early October 1719 and later opened a bureau d'achat et de vente to continuously intervene in the market for its shares. These buybacks were financed with zero interest loans.

By February 1720, around 800 million livres of banknotes had been created to purchase Mississippi Company shares. The decline in interest rates and increase in dividends seemed to justify the rapid rise in the share price. At the market peak in late 1719, the yield on government debt was 2% and loans for share purchases (margin loans) had the same interest rate, while Mississippi shares traded at around 50 times earnings and paid a dividend equivalent to 2% of the market price.

The Peak …

For a brief spell, the System delivered all that Law had promised. As he later recalled:

“The Prince was the head of a rich people, his revenues increased and the burdens on his people reduced. There were no longer uncultivated lands or workers without work. Peasants were fed and clothed and owed nothing to either King or master. Manufactures, navigation and trade increased and … credit was preferred and gained relative to specie.”

Law's personal investment in the company made him extremely wealthy, and many other people also became wealthy during this time as well. Paris was filled with people showing off their wealth through expensive clothing and jewelry, and there was a high demand for luxurious items such as tapestries and watches. While Law was skilled in financial matters, he did not focus on properly managing the company, which was the largest in history by market value and size. However, even if Law had been more responsible in his actions and management of the company, it would still have failed due to its unstable financial foundation.

… and downfall

It couldn’t be expected, but towards the end of 1719, the large amount of banknotes have caused a high inflation, evidenced by the nearly 100% increase in commodity prices. As people lost trust in the paper currency, money left the country. Law was faced with a difficult decision: he could either continue printing money to support the share price, potentially causing more inflation and currency failure, or he could remove the excess notes and risk collapsing the bubble.

Mississippi shares dropped significantly in February 1720 when the company's share trading office was closed. In an attempt to fix the situation, Law reopened the office and promised to maintain the share price at 9,000 livres, potentially issuing an unlimited amount of banknotes to do so. However, the French currency continued to weaken against gold-backed sterling on foreign exchanges. In May, Law changed his strategy again, announcing that the share price would be fixed at 5,000 livres, roughly half its previous peak, and that the value of banknotes would be reduced by half in relation to coin. This deflationary move caused riots, the storming of the Royal Bank, and the destruction of Law's personal carriage. The Regent nullified the decree and fired Law as finance minister, though he was later reinstated. All trust in the system was lost, and in December, Law resigned. The following month, just over a year after being appointed finance minister, Law left France, abandoning his fortune, family, and aspirations. His monetary experiment had ultimately failed.

All over again

Despite the fact that Law’s policies produced a surge of inflation and a great stock market crash, academics and central bankers warmly applaud his monetary notions as the essential principle underlying the decisions by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank today.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 resulted in economic and financial conditions similar to those in France after the death of Louis XIV. In response, monetary policymakers followed in Law's footsteps by lowering interest rates and purchasing large amounts of national debt with newly printed money. The Federal Reserve also implemented a policy of increasing asset prices by decreasing the discount rate. Like Law, who made Mississippi millionaires, these 21st century actions resulted in the creation of numerous billionaires. Similarly to the Mississippi bubble, monetary authorities blamed the irrationality of markets and the greed of bankers as the central causes of the crisis.

But, as Cantillon pointed out some centuries ago, when a national bank engages in quantitative easing and buys government debt, the newly printed money initially only affects financial assets and not consumer prices, gradually entering the broader economy.

Like Law, who never acknowledged the flaws in his system, central bankers exhibit a sense of infallibility as they continue to print money, manipulate interest rates, and inflame asset price bubbles. They ignore Cantillon's warning that grand monetary experiments often have unpleasant consequences and that there is no easy way out. In fact, the actions of central bankers today are reminiscent of those recommended by Law. It is likely that Law would be proud of his modern-day counterparts, such as Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi, and Christine Lagarde.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

References

Chancellor, E. (2022). The Price of Time: the real story of interest. Atlantic Monthly Press. NY

great piece, thank you!

A wonderful piece. Thanks for sharing.