#45 Rise and fall of Long-Term Capital Management

Brief notes on economic and financial history: Episode III. When a bunch of Nobel laureates thought that models could forecast the limits of human behaviour

In the late 1990s, a group of distinguished investment bankers and economists, including Nobel laureates, founded Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund that espoused a revolutionary investment approach based on complex mathematical models based on identifying and exploiting pricing discrepancies between related financial instruments. The fund's managers believed that these spreads would eventually converge, allowing the fund to generate significant profits.

However, their hubris ultimately led to their downfall, as the fund's spectacular collapse in 1998 highlighted the limitations of even the most sophisticated financial models when faced with the unpredictability of human nature.

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design”

“The creation of wealth is not simply a physical process and cannot be explained by a chain of cause and effect. It is determined not by objective physical facts known to any one mind but by the separate, differing, information of millions, which is precipitated in prices that serve to guide further decisions”

The Fatal Conceit - Friedrich Hayek

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

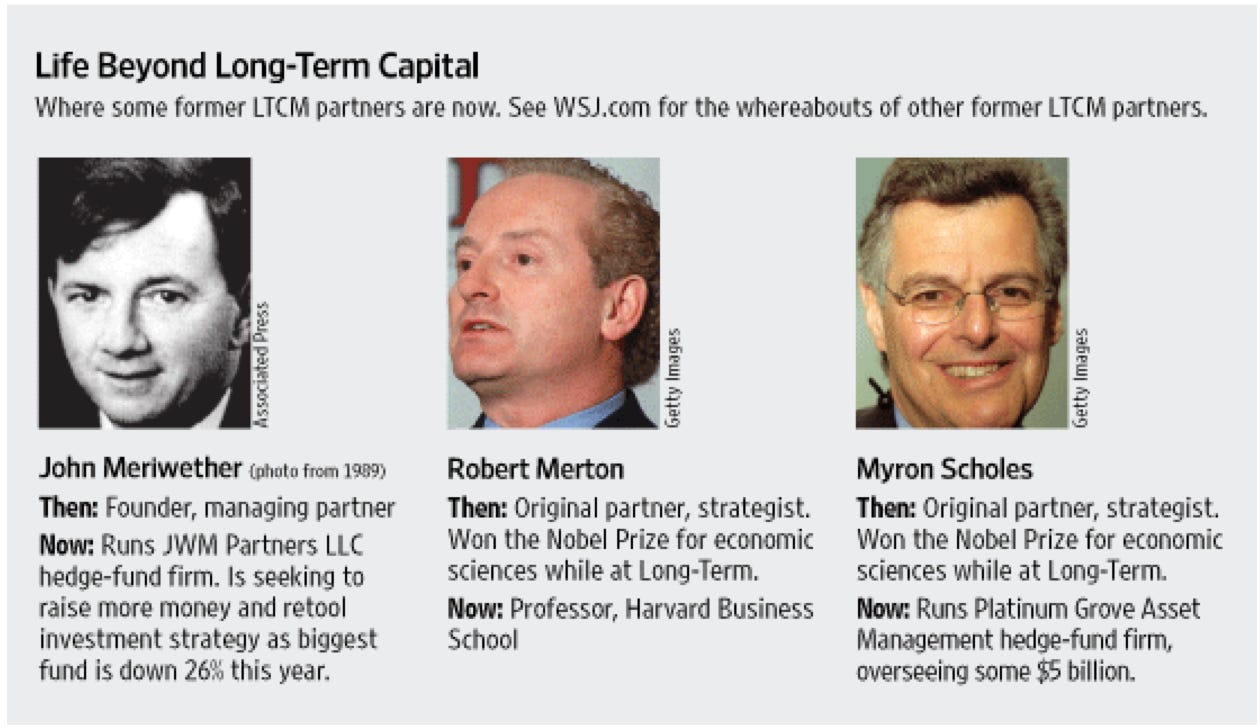

Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) was a hedge fund founded in 1994 by a group of highly successful financiers, including John Meriwether, the former vice chairman of Salomon Brothers, and two Nobel Prize-winning economists. The fund was based in Greenwich, Connecticut, and initially focused on arbitrage strategies.

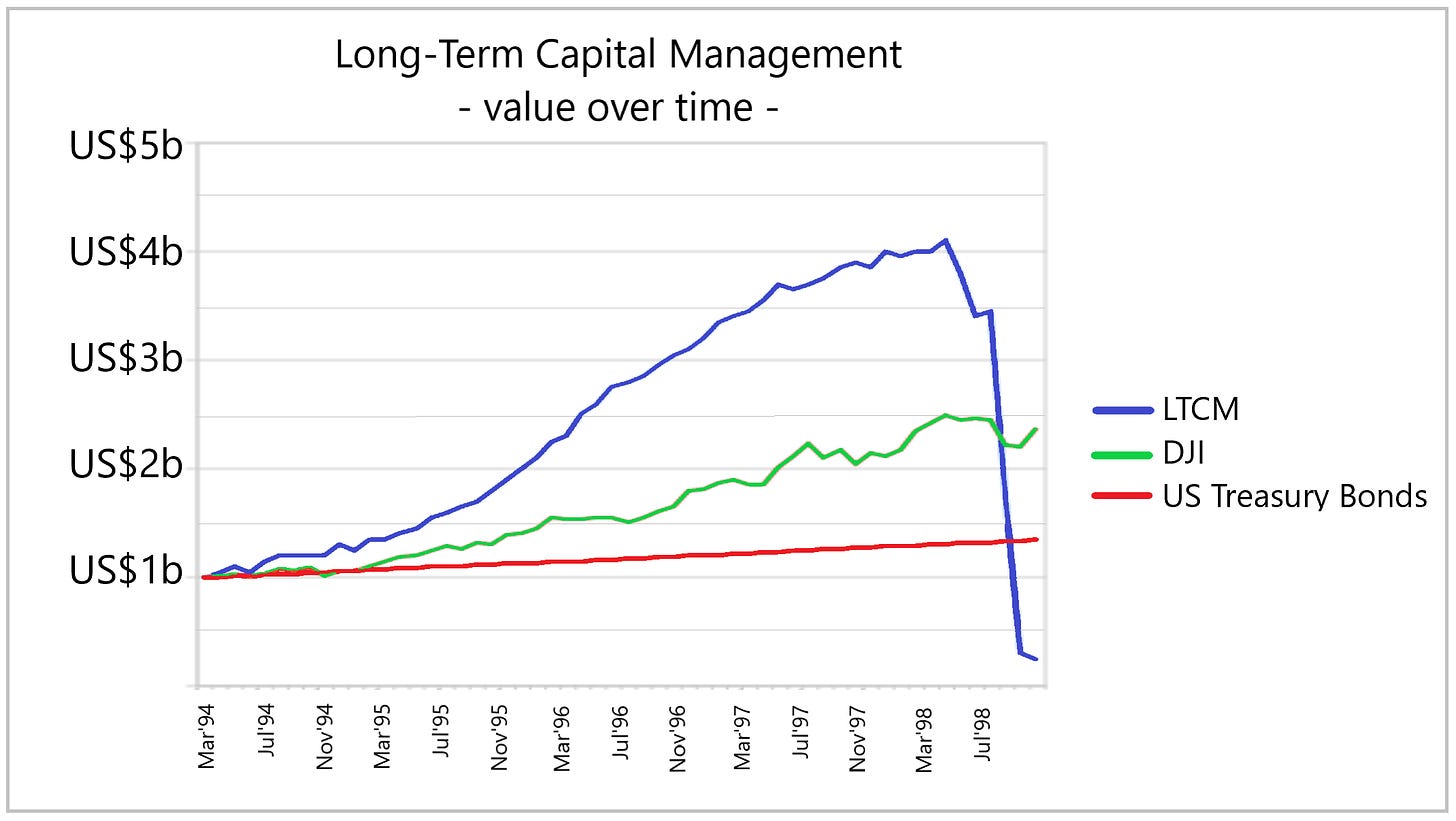

LTCM was highly successful in its early years, achieving annual returns of over 40% in its first few years of operation. The fund quickly grew in size and reputation, attracting a large number of investors and gaining the confidence of the financial community. However, in 1997, the Asian financial crisis hit, and LTCM suffered losses as a result. This setback was followed by another major blow in 1998, when the Russian government defaulted on its debt, sparking a financial crisis in the country. These events ultimately triggered a chain of reactions that involved, among others, the Fed, Berkshire Hathaway, and Warren Buffett, ultimately leading to the downfall of LTCM.

The origins

Our story today begins with the Salomon Brothers' Treasury bond scandal in 1991, the same scandal in which Buffett had to take control of Salomon put things in order. At that time, John Meriwether was the vice chairman and responsible for a special fixed income arbitrage unit. Meriwether was generating extraordinary profits for Salomon at that time, with special compensation conditions for his group to keep them in the bank and prevent them from creating their own firm.

One of Meriwether's subordinates, Paul Mozer, submitted illegal bids for U.S. treasury securities, which led to the scandal. Despite Meriwether's apparent lack of involvement, as the responsible party and despite indications of malpractice, he trusted Mozer. When everything came to light, Meriwether was one of the first heads to roll under Buffett's leadership (which did not prevent Meriwether from approaching Berkshire a couple of years later to raise funds, to which Buffett politely declined).

Gradually, some of his former colleagues followed him into his next project, a hedge fund he called Long Term Capital Management, with which he intended to repeat the success he had had at Salomon. Only this time he wouldn’t have the limitations he had faced at the investment bank. Meriwether had a great reputation on Wall Street, and had made a lot of money for those who had approached him. He was also one of the first people on Wall Street to recruit mathematicians and physicists from schools like MIT and Cal. Tech and turn them into bond traders. This allowed him to recruit partners such as, among others:

Robert Merton: Nobel laureate in economics and a professor at the Harvard Business School, who was a key architect of the mathematical models used by LTCM to predict market behavior.

Myron Scholes: Nobel laureate in economics and a professor at Stanford University, who co-authored the Black-Scholes model for pricing options, which was a key component of LTCM's investment strategy.

David W. Mullins Jr.: former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve. We will see later it was not casual.

Eric Rosenfeld: former vice-president at Goldman Sachs.

Victor Haghani: former Salomon Brothers executive who joined LTCM as co-head of its London office.

Greg Hawkins: former managing director at Salomon Brothers.

Despite having this cast of titans, the beginnings of any business are not easy, and LTCM was no exception. Especially given the fact that for the privilege of having their money managed by "Masters of the Universe," LTCM would also charge investors more than the usual hedge fund fees, a respectable 2-25%. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bask in the glow of such financial geniuses.

Additionally, the hedge fund was notoriously secretive and imposed strict limitations on fund withdrawals, forcing investors to lock up their minimum $10 million initial investment until the end of 1997, all of which made potential investors wary. However, despite these obstacles, LTCM maintained close relationships with almost all major investment banks, who were eager to do business with the legendary traders. In these relationships, despite the hedge fund not disclosing its counter positions, the banks accepted to lend money to LTCM at very low interest rates.

Ultimately, the allure of potentially immense profits proved too tempting for investors. By 24 February 1994, the day LTCM began trading, the company had raised just over $1.01 billion in capital.

Operative “too smart to fail”

LTCM's primary investment approach involved identifying pairs of bonds that typically maintained a predictable spread between their prices, and then leveraging the spread to bet that the two prices would converge when the spread widened further. This strategy was commonly referred to as convergence trading and involved utilizing quantitative models to exploit pricing anomalies in the relationships between liquid securities across various nations and asset classes.

It should be noted that all these models were based on statistics and past experiences. In other words, they were modelling the past and they were trading expecting future market behaviour will be confine to past events, with some certain degree of deviation.

LTCM invested in an array of assets and strategies, being some of them:

Fixed Income

a) Arbitrage: The fund looked for opportunities to profit from temporary disparities in prices of related assets, capturing small profits from carefully hedged positions by buying the cheap security and shorting the expensive one. LTCM's rationale was based on historical performance of converging spreads between risky and risk-free assets.

b) Market integration in Europe: LTCM believed that as Europe integrated its markets, it would have to ensure that the 11 member countries would eventually need to align their interest rates.

Equities

Given the success, LTMC believed that the strategy was transferable to equities. By June of 1998, the fund owned $539.2 million worth of stocks in 76 companies.

a) Pairs trading between related stocks: LTCM held a $2.3 billion position in Royal Dutch Petroleum and Shell Transport, with the latter historically trading at an 18% discount to the former. LTCM exploited this by purchasing shares of Shell Transport while simultaneously selling shares of Royal Dutch, betting that the discount would eventually decrease and Shell's value would increase relative to Royal Dutch.

b) Risk Arbitrage: Instead of buying stocks outright, LTCM used total return swaps with Wall Street firms to bet on the merger of Citicorp and Travelers Group. The swaps allowed LTCM to leverage returns while shifting most of the risk to its trading partners.

c) Market Volatility: LTCM bet when market volatility was abnormally high, assuming that the market would return to historical norms.

By 1997, the fund's debt had ballooned to approximately $125 billion, with a balance-sheet leverage ratio of 25 to one. This figure did not accurately reflect the fund's actual credit risk, as it had engaged in high-risk off-balance sheet derivatives contracts, which further amplified its leverage.

FOMO

New contributions and reinvested earnings had raised LTCM's capital to around $7 billion by 1997 from the original $1 billion. These guys had found the philosopher's stone. And the results were nothing short of remarkable. LTCM achieved a return of 20% in its first 10 months of 1994, 43% in 1995, 41% in 1996, and a respectable 17% in 1997. All of this with little to no volatility!

It is only human nature that managers’ greed began to outweigh their sense of logic. LTCM’s managers concluded that the fund had too much capital given its investment opportunities, forcing many newer investors to withdraw their money. Investors, with many investment banks among the ranks, were outraged. However, opportunities were fading in the market, and reducing the leverage was not an option. The profitability of the strategy only came associated with the leverage. Therefore, the fund started new strategies outside their overall market neutral approach. By year-end 1997, the fund had $4.7 billion in capital, of which $1.5 billion belonged to insiders.

The crisis

With this brand new expanded strategy, LTCM began investing in emerging-market debt and foreign currencies. In 1998, before the Russian financial crisis, LTCM posted a 10% loss, its biggest monthly loss to date. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 had affected markets beyond Asia, raising investor concerns about all markets heavily dependent on international capital flows, which shaped asset pricing in markets outside Asia too. In May and June 1998, returns from the fund were negative, and the exit of Salomon Brothers from the arbitrage business in July 1998 aggravated the situation. This was followed by the Russian financial crisis in August and September 1998, when the Russian government defaulted on its domestic local currency bonds. LTCM lost $1.85 billion in capital by the end of August and was forced to liquidate some of its positions, suffering further losses. This forced liquidation resulted in LTCM losing $286 million in equity pairs trading.

Capital is fearful and flees when the bells of war, or in this case, crisis, ring. Although not directly exposed, they were exposed to the temporal irrationality of the markets. And all of this highly leveraged. What happened next was simply a chain reaction.

As investors sold foreign, riskier securities, their prices fell while rates rose. Conversely, US securities’ prices rose and rates fell. Instead of narrowing, the spreads between risky and risk-less securities widened in virtually every market around the world, crushing Meriwether’s fund.

When spreads widened in a disorganized tumbling market, gains on short positions were not enough to offset gains on long ones. Lenders demanded more collateral, forcing funds to either abandon the arbitrage plays or to raise money to meet margin calls by selling securities at fire-sale discounts. By September 2nd 1998, LTCM’s capital had fallen by 44%, to $2.3 billion, while still carrying over $100 billion in debt.

LTCM’s investors were mainly the partners of the fund, but also the big investment banks and large brokerage firms which where also lending the leverage capital to LTCM. A bankrupt LTCM would have forced many banks to declare huge losses on their gambles (many had after all unsecured loans with the firm).

Fed comes to rescue

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York swooped in to save the day when Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) found itself in dire straits. After all, why let a multi-billion dollar hedge fund fail when you can just organize a bailout? When LTCM failed to raise more funds, Goldman Sachs, AIG, and Berkshire Hathaway made an offer to buy out the fund's partners for a measly $250 million, inject $3.75 billion, and operate LTCM within Goldman's own trading division. The offer was a classic Warren value play compared to the $4.7 billion the firm was worth at the beginning of the year, but hey, beggars can't be choosers, right? Mr. Buffett gave LTCM's John Meriwether less than an hour to accept the deal. Predictably, proud Meriwether didn’t accept. He knew his head was gonna be chopped right away for the second time.

Seeing no other options, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York organized a bailout of $3.625 billion by the major creditors. The main banks contributed a total of $3.25 billion, while Société Générale chipped in $125 million. Paribas and Lehman Brothers also contributed $100 million each. Bear Stearns and Crédit Agricole declined to participate, presumably because they were too busy counting their own profits to bother bailing out someone else.

To facilitate the bailout, the Federal Reserve also took several other actions. It lowered interest rates to encourage borrowing and provide liquidity to financial markets. It also provided short-term loans to financial institutions to help them meet their funding needs.

In return for their generosity, the participating banks got a 90% share in the fund and a promise that a supervisory board would be established. LTCM's partners received a 10% stake, which was worth about $400 million at the time. However, this money was completely consumed by their debts, as they had previously invested $1.9 billion of their own money in LTCM, all of which was wiped out.

In summary, the Fed's swift action ensured that LTCM didn't have to face the consequences of its risky investments. And why should they, when they can just pass the buck to other banks and leave them holding the bag? After all, it now seems clear it was just a testing environment for what was coming in 2008.

Ironically enough, or not, nine months before LTCM failed, Merton and Scholes shared the Nobel prize in economics. Merton, Scholes and Stanford's William Sharp (famous for developing the sharp ratio to measure risk) are some of the founders of modern finance, which attempts to apply quantitative techniques to market analysis. This same techniques are still widely use to measure risk, value options, etc.

When everyone is making millions, nobody asks why. Risks are relativized. This happened in 1929, the Nifty Fifties, with LTCM, the dot-com bubble, 2008, post-COVID, and it will certainly happen soon again. It is just human nature.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

References:

Lowenstein, R. (2000). When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management. Random House.

Karbasfrooshan, A. (2020). The Case of Long Term Capital Management. Link

Great take, thank you! The documentary is a must see also. Cheers!