M&A always gets buzz in the public markets. Many investors fell in love with "compounders", companies that spend a large amount of their free cash flow buying inorganic growth. The market many times assumes that these companies will generate extraordinary value. Investors have been and are willing to pay high multiples to become shareholders, which has led to the re-rating of many of them in recent years. However, any empirical study in this area shows the opposite is the norm. Most M&A transactions destroy shareholder value.

The challenge for investors, therefore, is to ensure that the acquisitions done by managers are among those that do create value for shareholders. To that end, this series provides a framework for analyzing how to assess whether past and future acquisitions create enough value depending on our opportunity cost. It discusses the archetypal approaches that are most likely to create value, as well as some other strategies that are often attempted but have longer odds of executing successfully.

"I will tell you a secret: Deal-making beats working. Deal-making is exciting and fun, and working is grubby. Running anything is primarily an enormous amount of grubby detail work. Deal-making is romantic, sexy. That's why you have deals that make no sense." - Peter Drucker

“Many corporations that consistently show good returns both on equity and on overall incremental capital have, indeed, employed a large portion of their retained earnings on an economically unattractive, even disastrous, basis. Their marvelous core businesses, however, whose earnings grow year after year, camouflage repeated failures in capital allocation elsewhere” - Warren Buffett

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

It is surprisingly difficult to find resources with which to learn how to properly analyze whether acquisitions generate value or not. In general, it might make sense because the results of acquisitions will be seen in the future, and when this time arrives, companies often do not disclose the necessary information we would need to make a full assessment. However, it is not impossible and we will try to break it down here.

An acquisition is a capital allocation decision that has the same characteristics as that of a stock market investor. Exactly the same. Just as most investors are bad investors and are driven by emotions, what makes us think that CEOs act any differently?

In today's post, we will focus on some basic, but very important concepts when dealing with analyzing acquisitions.

In part II next week we will step into the boots of the CEO and CFO, and look at different types of potential acquisitions. We'll roll up our sleeves and get to work with the numbers. We will look at the expected returns we can have to understand the decision-making process, and see all the pitfalls that can exist along the way.

In part III we will put on our investor hat, and analyze acquisitions of various companies by different methods, in order to measure the capital allocation skills and results of various companies based on past acquisitions.

Creating value through M&A is challenging

M&A is one of the 5 capital allocation possibilities for companies. For many companies, acquisitions are the chosen way to allocate capital and pursue strategic objectives. Indeed, companies spend more on M&A than on any other capital allocation alternative.

It is surprising to read this while it is well-known that value creation through M&A is very difficult for an acquirer. For a start, if the price paid is too high, the buyer may not recoup its investment even if the deal makes strategic sense. Think of it this way. If you invest in a company at a 500x earnings multiple, you have a tiny little chance to obtain a good performance long-term, even if the business is excellent.

Secondly, acquisitions cause disruption in the company: team integration, products, facilities, and many more. It is simply costly, reduces productivity, and impacts the margins in the short term. It also requires a lot of management attention that is lost from the core business.

Finally, mergers and acquisitions require an upfront payment for future profits. It is an investment and has an opportunity cost, which is also very costly to reverse.

So why do so many managements love to do so many M&A deals?

A.T. Kearney surveyed investor relations professionals about the metric they believed that stakeholders, including executives, sell-side analysts, and investors, care about most in assessing M&A. Three-quarters of the respondents said that stakeholders place a “strong emphasis” on earnings per share (EPS) accretion or dilution.

What nonsense!!!

It really gets on my nerves. This answer is simply stupid and has a non-existent hurdle rate. Almost all M&A deals are accretive to the EPS of the buying company. The same applies obviously to FCF. It is like saying I would be happy if I get 1$ dollar after having invested 1000$ in one company. The same level of lucidity and stupidity. Not surprising to see later the results below.

Archetypes for value-creating acquisitions

It is really difficult to identify specific profiles that create value based on empirical analysis, but I would say typically successes cases could be gathered around based on 2 different categories:

Acquisition strategy

Companies typically talk up all kinds of strategic benefits from acquisitions that are really all about cutting costs. In McKinsey’s experience, the strategic rationale for an acquisition that creates value for acquirers typically fits one of the following 5 archetypes:

Improve the performance of the target company: buy a company and radically reduce costs to improve margins and cash flows. Keep in mind that it is easier to improve the performance of a company with low margins and low return on invested capital, especially when average peers can do it. The strategy of many Private Equity firms.

Create market access for the target’s products: the case when relatively small companies with innovative products have difficulty accessing the entire potential market for their products. For instance, small pharmaceutical companies typically lack the network, the brand, and the large sales forces required to access clients.

Acquire skills or technologies more quickly or at a lower cost than they could be built in-house: Apple bought Siri in 2010 to enhance its iPhones, and later in 2014, Novauris Technologies, a speech recognition technology company, to further enhance Siri’s capabilities.

Exploit a business’s industry-specific scalability: economies of scale can be sources of value in acquisitions when the unit of incremental capacity is large or when a larger company buys a subscale company. For example, the cost to develop a new car platform is enormous, so auto companies try to minimize the number of platforms they need. The combination of Audi, Porsche, and VW allows the three companies to share some platforms, for example, the Audi Q7, Porsche Cayenne, and VW Touareg. But careful especially for large acquisitions. Large companies often are already operating at scale, in which case combining them will not likely lead to lower unit costs.

Pick winners early and help them develop their businesses. YouTube or Instagram cases. I think there is no need to explain further.

I can imagine most of you are already thinking about many cases when one of these strategies did not work. There are many. To achieve the expected synergies at reasonable prices is really challenging.

Acquisition size and recurrence

Beyond the five main acquisition archetypes just described, many times it is just as important to consider the nature of the companies doing them. It makes sense that we can expect different results from companies whose growth model is acquisition-driven, used to making integrations, with a department focused solely on sourcing new deals, than one that does it sporadically. Not that this ensures success, but it might indicate a place to start looking.

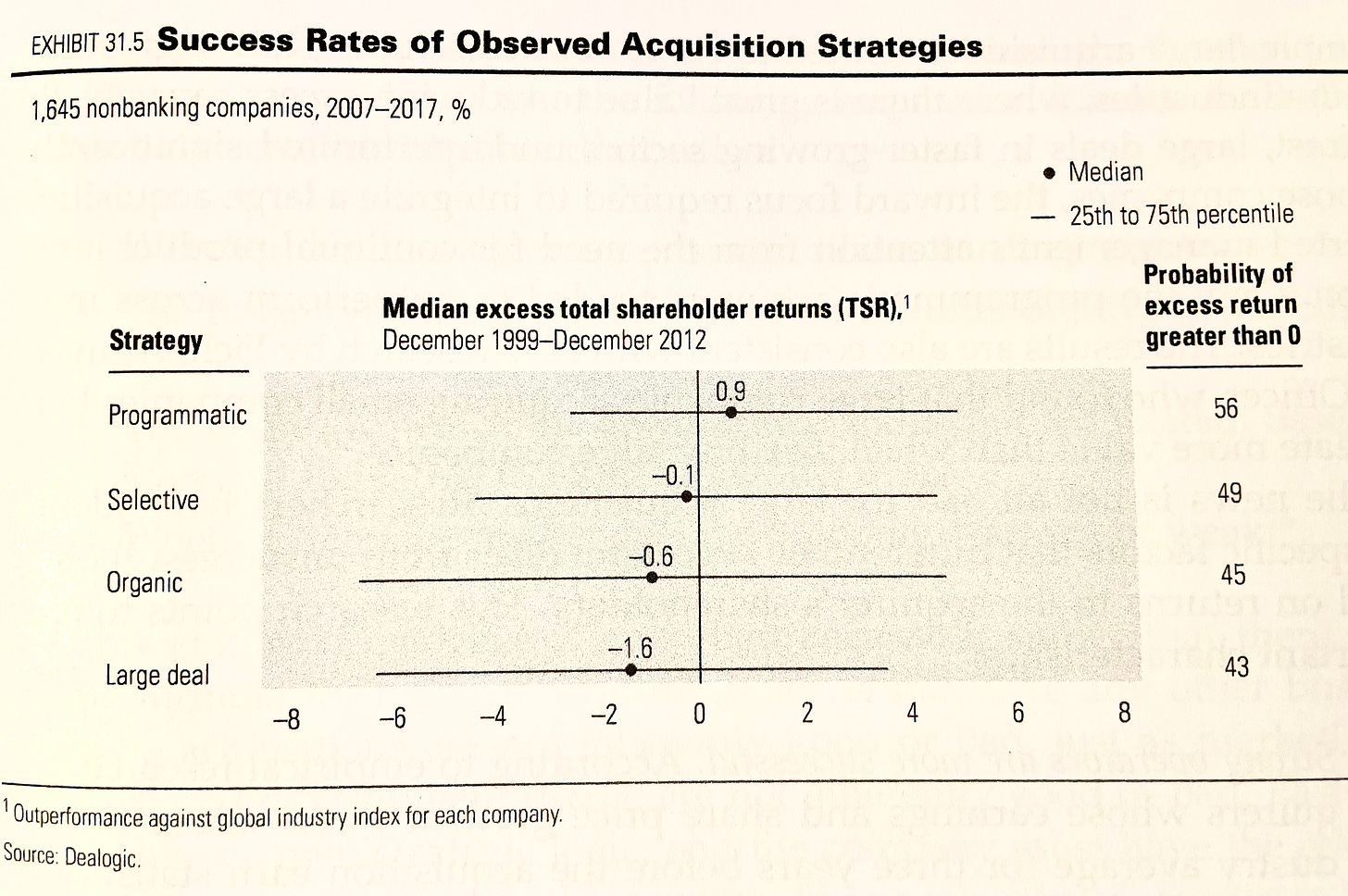

While success stories can be found in each of the categories McKinsey sets out in the image below, the reality is that most of the value creation stories are found in companies that maintain an ongoing strategy of small, tactical, and programmatic acquisitions. Hakansson (2022) captures them very well below and devotes his interesting little book, Serial Acquirer Primer, to describing the qualities of these types of companies. I invite you to visit his website and download it if you want to go into more detail. Link in the references.

Some final considerations

Before we finish today and we get down to business next week, I wanted to share some thoughts with you. As we have seen, making acquisitions is a capital allocation activity. It requires capital allocation skills. To achieve good results, it needs the mindset of an investor, not that of an operator executive. In other words, it requires a deep understanding of the basic concepts of value creation. This is less common than it seems in management teams, as we have seen in the response to how they valued the success of acquisition by increasing EPS.

We always hear managers, and even investors, talking at best, about margins. In earnings presentations, we always hear about P&L results and sometimes, if we are lucky, about the cash flows. But we always forget about the balance sheet.... little is said about the time value of money, hurdle rates, IRR, or return on capital.

We have this question pending from above: So why do so many managements love to do so many M&A deals?

Doing M&A is fun. Yeah, really. Allocating capital is fun (especially when it is not yours). It makes you feel important. It is exciting to be assessing new acquisitions, rather than coming down to the assembly line and trying to create some efficiencies in the processes or contacting clients to make new sales. It’s in human nature, there is nothing bad about it. Only it might lead to wrong decisions.

Furthermore, it is an ego boost. It happened to kings and emperors centuries ago. They wanted to expand their kingdoms and empires, no matter the costs. Now, CEOs want to rule over big companies.

Incentives. It is surprising to see how many management teams are incentivized to grow, rather than to create value with profitable growth. We have a whole series about it in posts 34, 35, and 36.

Low-interest rates environment. The easy money policies set by central banks have decreased the cost of capital, so simply incentivize agents in the economy to “invest” with lower hurdle rates. We have seen it many times before in different posts, so I will leave it here.

Successful M&A is scarce. We could say it only happens in unicorn fairy tails. Hunting down these unicorns is also difficult. There are too many fake ones. Again, it is tricky to gather a checklist, but the ones below are some of the hints to find them.

Next week we will step into management shoes and play the game of forecasting synergies, case scenarios, and IRR.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

References

Hakansson, G. (2022). Serial Acquirer Primer: The light book on assets. www.acquirers.com @SerialAcquirers

Mauboussin, M.J., Callahan, D., Majd, D. (2017) To Buy or Not To Buy: A Checklist for Assessing Mergers & Acquisitions. Credit Suisse.

Koller, T., Goedhart, M., Wessels, D. (2020) Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies. Wiley. 7th edition

Waiting for the second part! Congrats 🙌🏼

thank you, appreciate, great take!