#43 Mergers & Acquisitions II

A framework to assess value-creation deals: stepping into management shoes

We ended last week saying successful M&A was scarce. How is it possible then that we have experienced such frenetic activity in the markets over the last decade? To answer this, we will analyze acquisitions from the perspective of the management of the acquiring company. We will model some projections to justify them and we will identify the errors that are often made and see how they influence the returns. All in order to learn where to look and try to avoid them in our journey as investors.

“While deals often fail in practice, they never fail in projections – if the CEO is visibly panting over a prospective acquisition, subordinates and consultants will supply the requisite projections to rationalize any price.” - Warren Buffett

"Buying another company based on the perception of opportunities for cross-selling and other intangible benefits generally represents a much higher level of risk than I believe is justified. Therefore, I concentrate on eliminating redundancies, which measurably reduces the capital required to run the business. Redundancies are much more predictable and transparent than theoretical opportunities to add value." - Sam Zell

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

Have you ever considered what is the value creation/compounding targets of the companies you are invested in? We might invest in a company for the long-term with a goal of achieving a 15% profitability, however, you may not be aware that the management has a goal of generating a 10% return on acquisitions they make. This is a common situation among many compounders. If the entire free cash flow generated by the company is reinvested with the goal of achieving a 10% return, what performance do you believe you will have as a long-term investor?

Nevertheless, before starting to dig into it, I believe it is important to understand what are actually the dynamics and processes that lead a company to make acquisitions.

A company's strategy is supposedly determined by its board of directors. Often this is ignored or deemed unimportant by many, but the board of directors acts as representatives of the shareholders to dictate the company's strategy and make important decisions. The management team's role should be simply to execute that strategy. What often happens is that the board of directors has so little "skin in the game" that their incentives are not aligned with those of the shareholders and they make decisions influenced by the management. Regardless, a board should define its strategic capital allocation objective. If this includes reinvestment through acquisitions, either sporadically or recurrently, the management team gets to work.

The board determines what types of companies shall be explored, what type of profitability or hurdle rates should be sought in acquisitions, what type of synergies, etc. After that is set, the ball is in the management's court. Whether with an internal M&A team or with the help of external consultants, they start to scan the market and speak with companies that might be interesting and willing to sell.

Due diligence processes are more or less rigorous. Terms are agreed upon. A business plan is made, and a financial model with the expected return is prepared. The board approves (if required) and the acquisition is executed. Now it is the time the integration process begins, while financial projections and expected synergies are tested.

Please note that the process, although I have simplified it greatly, has infinite potential ownership, responsibility, and incentives faults and pitfalls. All of which can be further exacerbated by a perverse incentive scheme (there are companies that incentivize their management to close deals!).

Today we will focus on those financial models that are made to justify acquisitions. As investors do their due diligence on companies and DFC to estimate their expected profitability, the same is true for a company making acquisitions.

Understanding the drivers for IRR

The internal rate of return (IRR) is a metric used to evaluate the potential profitability of an investment. It is determined by finding the rate of return that makes the present value of future cash inflows equal to the initial cash outflow (the investment). This metric is often used to evaluate the potential profitability of a new project or acquisition.

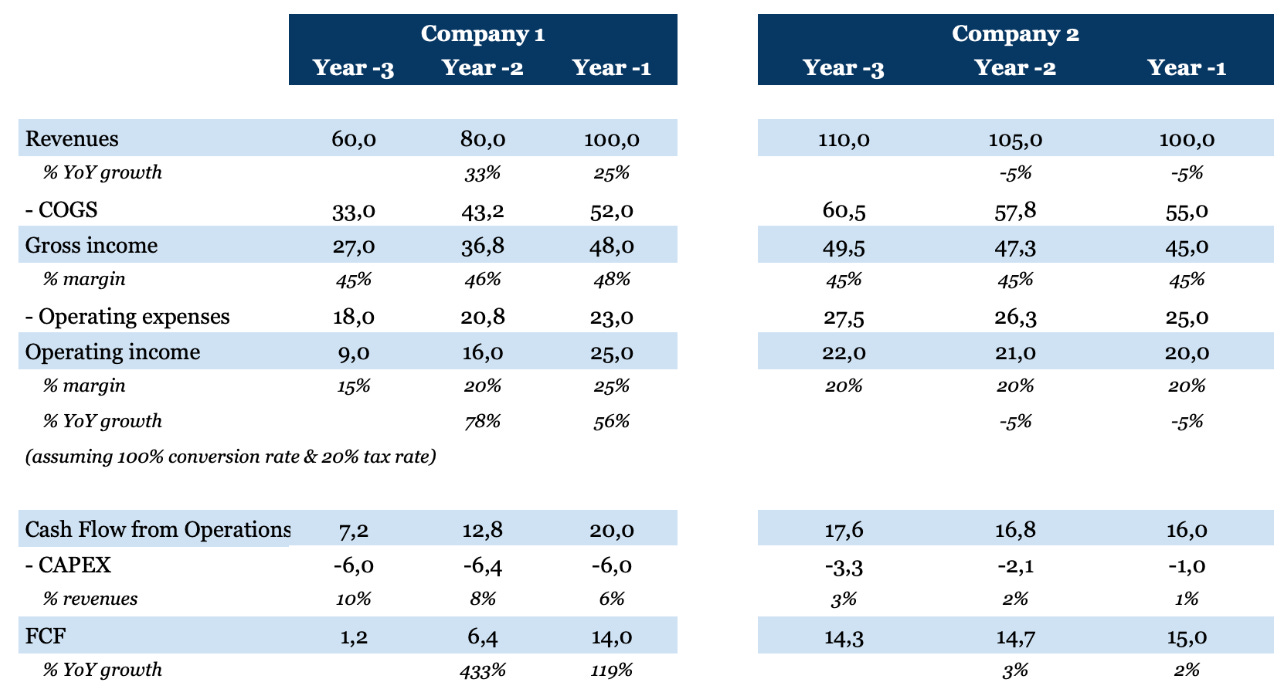

Let us imagine the fictitious case of Edelweiss Group, whose market capitalization is $10 billion. Last year, they generated $350 million in free cash flow. At the moment, they are evaluating different options for allocating this capital and have decided to explore two possibilities for inorganic growth. The team has identified two companies with the following results over the last three years:

Company 1 has had very high growth in recent years because it is in a sector with strong tailwinds. Additionally, they believe that it will continue to grow in the future, although they understand that the increase in margins and FCF will not be able to keep up with the pace of recent years because it is already quite optimized. In summary, they assume that if they acquire it, they will be able to grow the FCF between 10% and 20% annualized. Of course, being a growth company, the price the company is asking for is quite demanding: 350m, which is equivalent to 3.5x revenue or 25x FCF. They see the valuation as quite reasonable given the quality and projections.

Company 2, on the other hand, is in a mature industry and has been gradually reducing its revenue in recent years. It is quite optimized and is able to maintain margins. It is not investing much back into the business, so they have even managed to marginally increase the FCF. The price is also much lower, only 75m, 5x FCF, but of course, the team estimates that this FCF will gradually decrease by about 10% per year. In the best case, they would be able to maintain it. The truth is that acquiring a company in this situation is not very exciting.

What would you do if you were the management? Probably go for the first company, right? In the following table, you can see the numbers for the 2 companies:

Are you surprised? Now, imagine you are the management of a company in which you do not have much ownership, and you are given the choice between these two companies. Would you choose the company whose revenues are decreasing and that is in a declining and unappealing industry, or would you go for the new beauty? Food for thought.

Planning for an acquisition

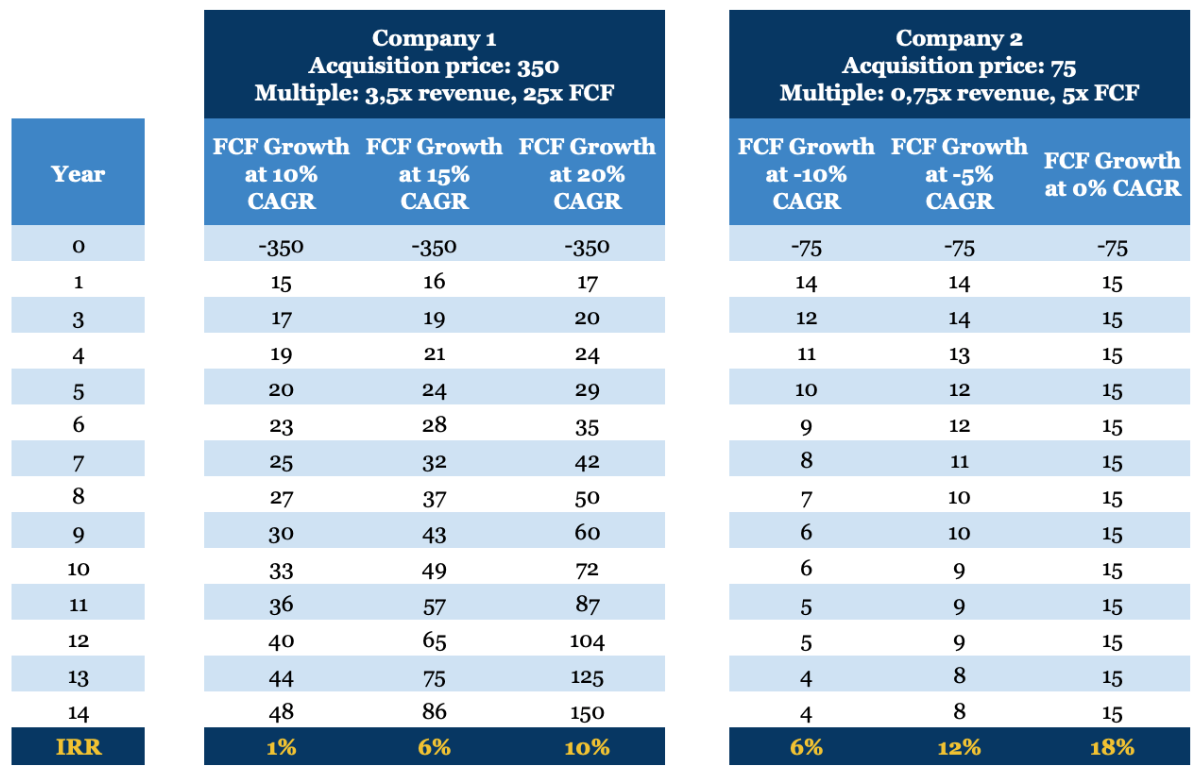

Example 1: Average industrial/service company at 10x EBITDA

Let’s continue with Edelweiss Group. Remember, 10b market cap. Edelweiss has been buying businesses from time to time in the last few years. Results have been so far mediocre, but the management believes they are getting better. They firmly believe the market has not been assessing correctly the potential of the group.

But there is a new potential acquisition. They ask for a 10x EBITDA price. (In the model below I assume EBITDA=EBIT+CAPEX).

If Edelweiss were to buy this business, they believe they will be able to increase revenues at a higher rate thanks to multiple cross and up-selling possibilities with new and former clients. They are also convinced they will be able to increase the gross margins by purchasing raw materials in bulk, thus decreasing the price. Additionally, they anticipate some operational leverage unifying some teams and removing duplicities, although, in the first two years, operating margins might be impacted due to internal restructuring and some integration costs. On top, a higher CAPEX is expected in the first year to improve the old machinery and drive new efficiencies in the future.

It is important to note that management will be seeking a minimum of 10% in this project. Keep in mind, this may not be sufficient for you given your opportunity cost, but management will believe it is creating value for investors because it is above their cost of capital. This is a potential delink in the principal-agent problem that not so many people consider.

Ultimately, the CEO presents to the Board of Directors the following model:

It is important to consider the level of subjectivity and manipulability present in projections. It is not uncommon for individuals to adjust margins and other factors to align with their desired return on investment. However, it is crucial to ensure that the incentives of the CEO and other decision-makers are aligned with the acquisition and the return it generates. Intrinsically, management can believe the acquisition is going to be good for the company, even if the numbers are not there.

Take a look at how difficult is to achieve a 10% return from an acquisition at “only” 10x EBITDA. Double-digit growth is required, margins expansion, while not having any recession year in between. Quite a challenge. Now imagine the cases where higher multiples are paid…

What could go wrong from here

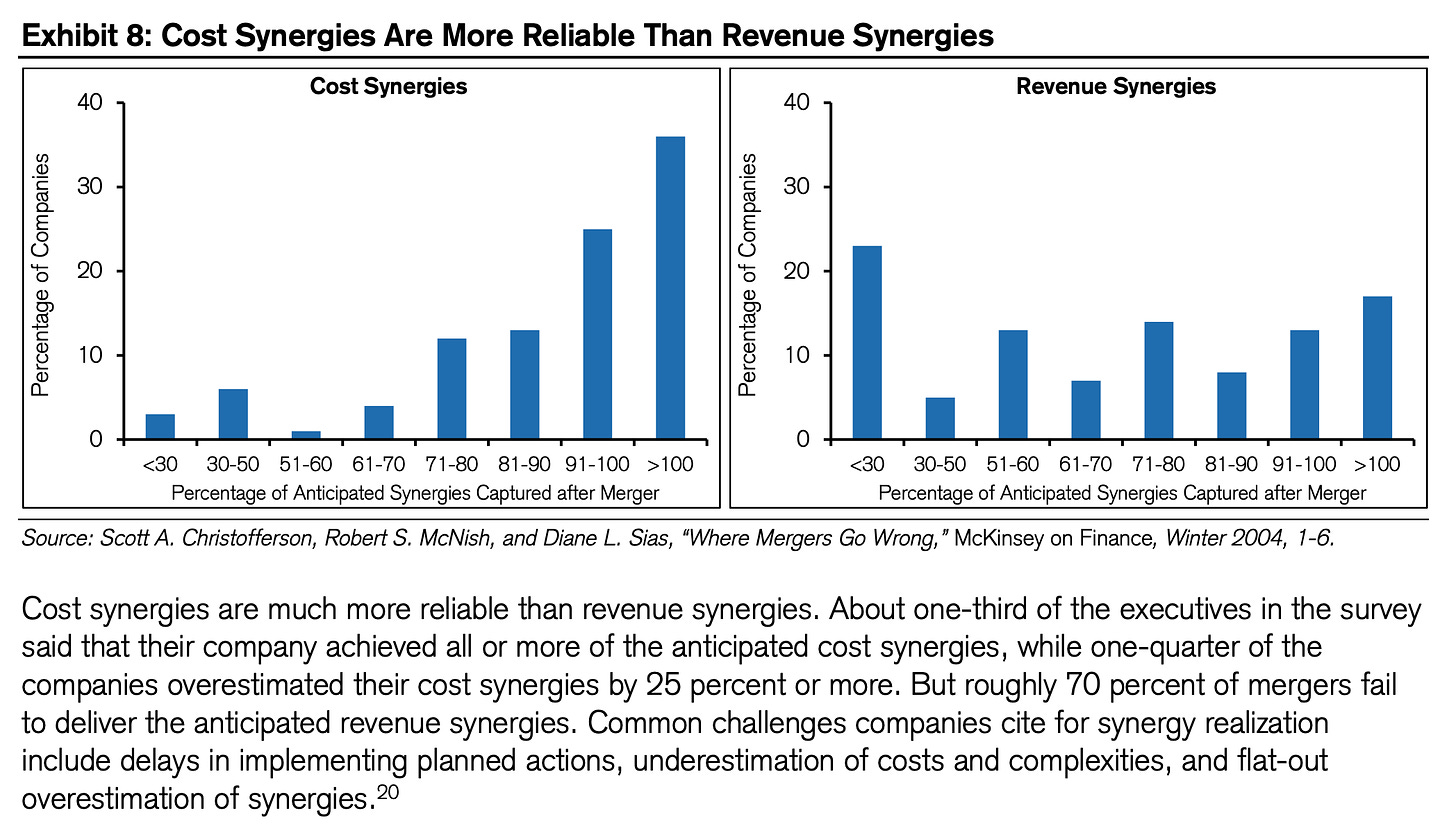

It is not a secret that models, projected cost-reduction synergies, and especially, cross and up-selling don’t materialize in the same terms as companies were expecting. Many times, integration problems arise, which drain too much executive focus, while reducing it from the main business.

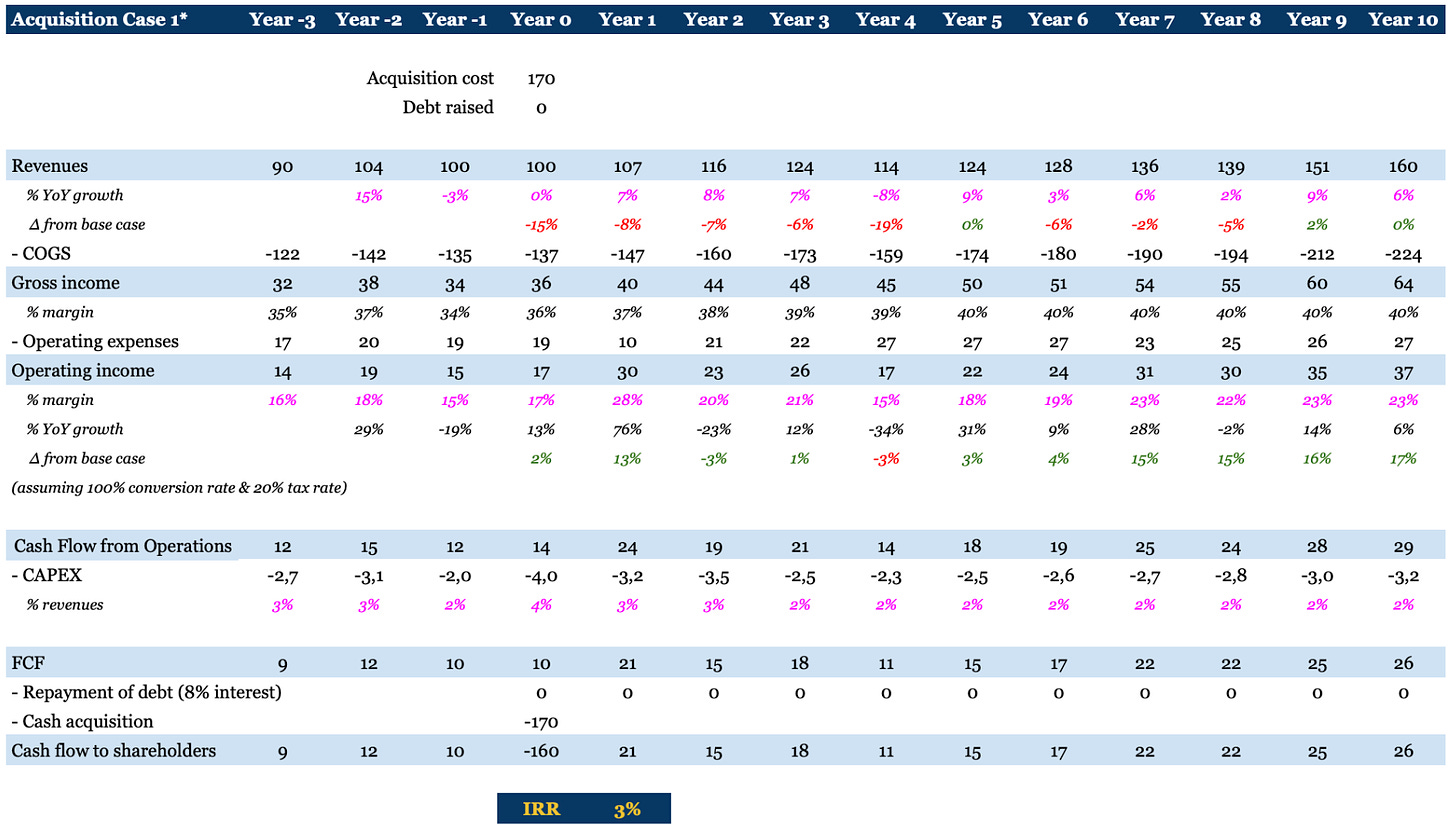

In the case and model before, what could go wrong? We can see the projections were not considering a recession at any point. Who would foresee a recession 4 years in advance? Not even Michael Burry! Yet, recessions happen in our intervened economy. Let’s consider Edelweiss facing a recession in year 4 and an impact of -8% in revenues. Operating synergies and integration were a huge success. They even outperformed the best estimations. However, as many times happen, revenue synergies were not captured and the growth rates achieved were not as expected. On top of it, with the extra focus on the integration between companies during the first year, the sales efforts had to decrease and no growth was achieved:

Note the fundamentals of the business continue to appear quite successful. Annual growth with the exception of the recession, significant improvement in all margins, and yet, the return on the 170 million from the acquisition, which was shareholder capital, has been terrible.

Nobody is ever right when projecting the future. Never, ever, has a model been right. If a company targets a 10% return, it might happen with a lot of chances that they never get it.

Example 2: Pros and cons of leverage

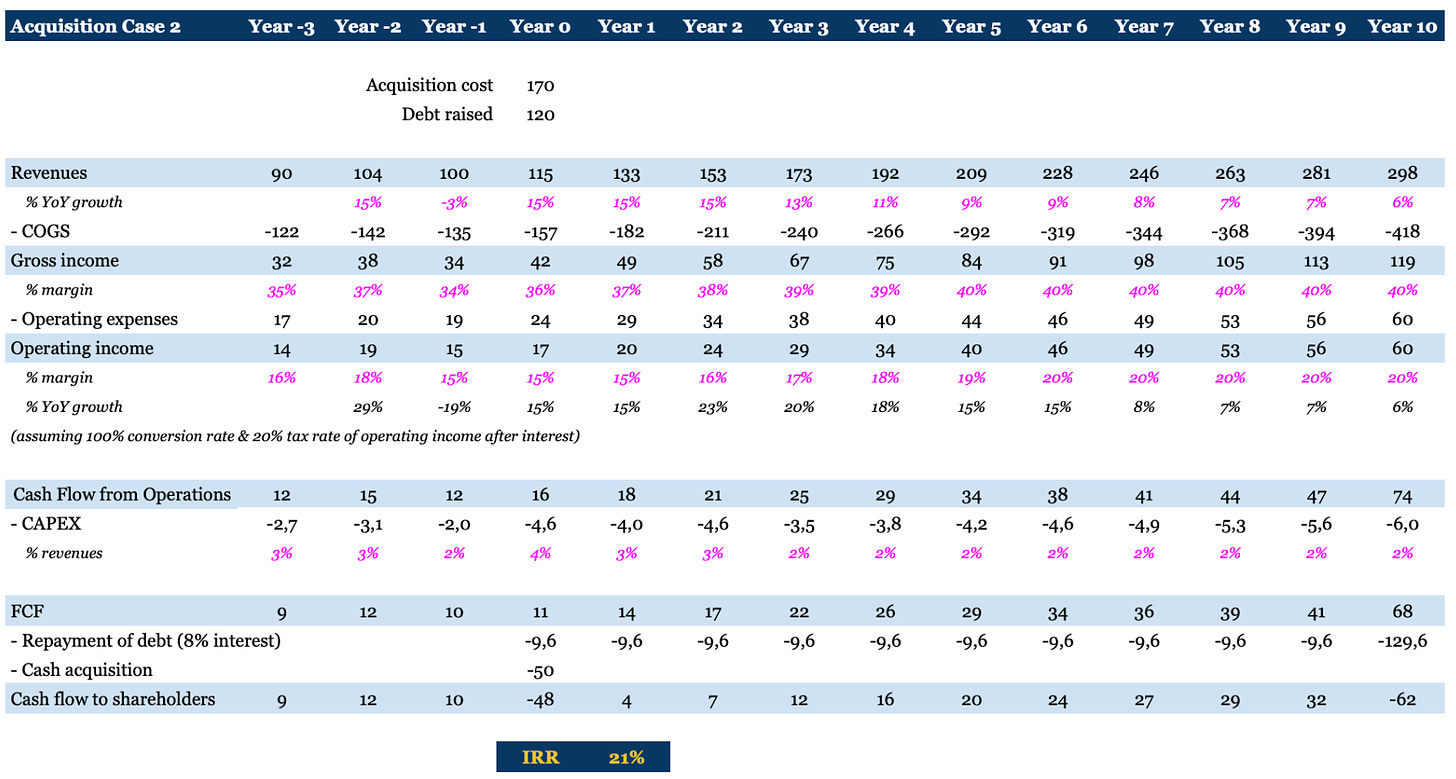

Frequently, companies utilize debt to maximize returns on acquisitions. As we all know, debt is a double-edged sword. Let's consider the aforementioned example, raising 120 million out of the 170 million in debt over 10 years at an 8% interest rate. The beauty of debt is that in addition to leveraging our investment, the cost of interest reduces our tax payments, and the conversion of operating income to CFO increases significantly. Additionally, the cash outflow for the initial payment is greatly reduced, thereby significantly increasing the IRR:

What could go wrong?

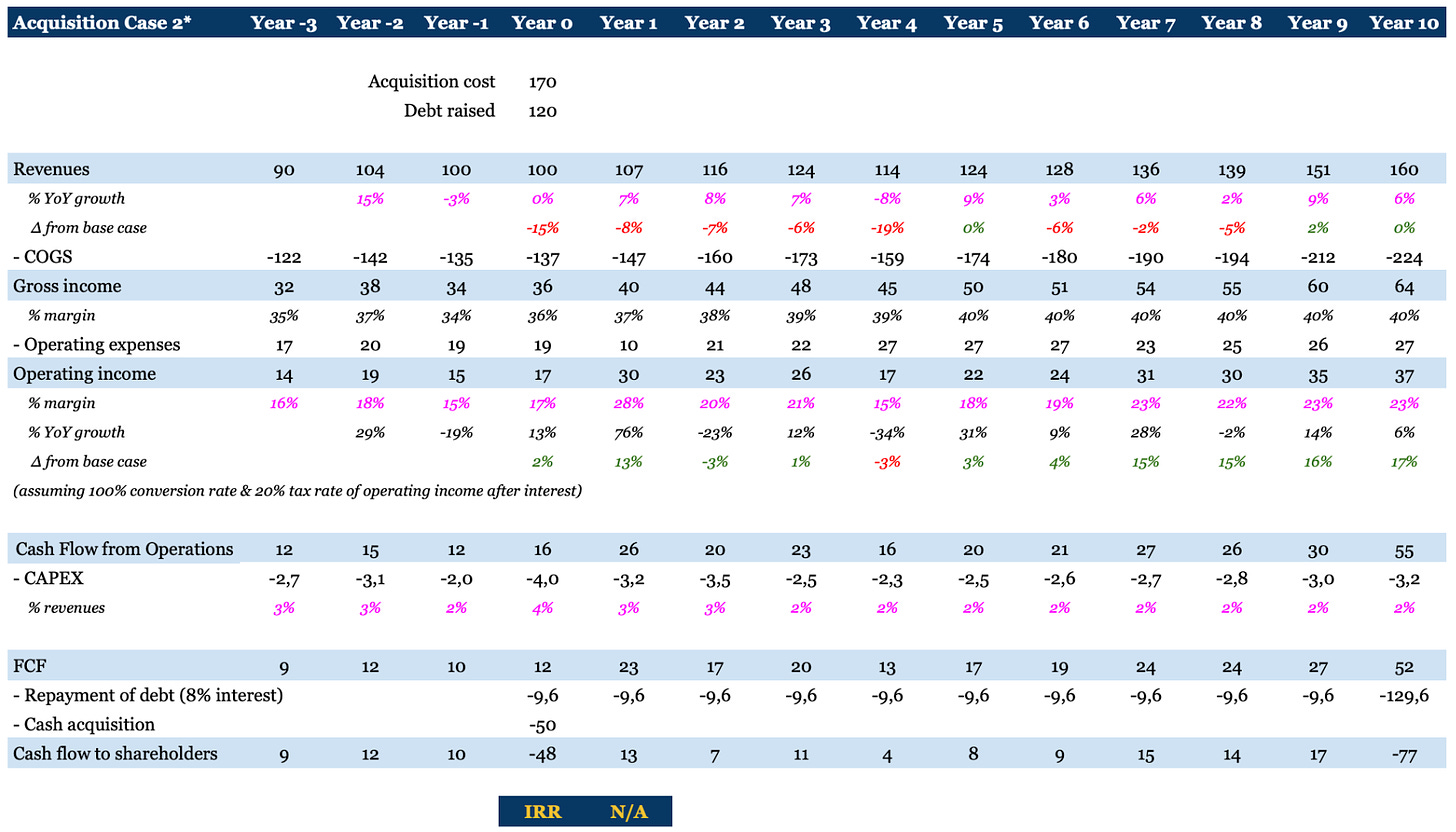

Projections using debt are even more dangerous than the most optimistic scenarios without it. The risk of leverage can become exponential. Let us consider the actual situation described previously, having utilized those levels of debt.

Pay attention not only to the fact that the sum of cash flows for shareholders becomes negative, but also that the Net Present Value of the cash flows is negative regardless of how small our discount rate is. And this is in a case that is in no way catastrophic. The company is still substantially better than when we bought it! Imagine a situation where the company's conditions deteriorate. Depending on the company's balance sheet, the company could potentially go bankrupt.

This type of highly leveraged operations are very common in Private Equity funds. These funds often invest in companies with very stable FCF in order to safeguard their interests. However, things can always happen, especially when a large part of the IRR comes from leverage and deferring that large cash outflow from the acquisition over time.

Many more aspects must be considered when making an acquisition. In addition to the use of debt or cash, the use of shares can also enter the equation, which complicates the analysis even further. Often, management uses shares because it reduces that initial cash flow and does not involve the risks of leverage. However, in exchange, the rights to future cash flows of shareholders are used, which can be more valuable than current cash. There is no rule to define what is better or worse because as with everything important in life, it depends on the particular situation. Nevertheless, it is important to see how the management and the board of directors think about these issues and if they understand the trade-offs and the generation of value.

Take also into account that here we are only considering the tangible aspects of acquisitions. In our last chapter, next week, we will study real-life examples. We will analyze the acquisition of Tiffany's by LVMH as if we were shareholders of LVMH at the time of the acquisition and had to verify the convenience or not of it. Similarly, we will look at some of the recent acquisitions of the German-Indian company Nagarro.

We will look at value creation and the track record of serial acquirers such as Constellation Software, or some of the Swedish representatives in this space such as Instalco or Teqnion.

Lastly, we will also look at some of the acquisitions of the Big Tech companies, such as the case of YouTube by Alphabet or Figma by Adobe. We will try to understand how the numbers are not the only important thing for these giants, but the competitive position, and how, even though the returns may not be adequate, the risks of allowing the competition to grow freely can imply greater destruction of shareholder value (as we may be seeing in the case of Meta with TikTok).

Stay tuned!

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

References

Mauboussin, M.J., Callahan, D., Majd, D. (2017) To Buy or Not To Buy: A Checklist for Assessing Mergers & Acquisitions. Credit Suisse.

Great writing! And I like your use of graphs to illustrate your points. 👍

thanks, thanks, thanks! such an amazing post